The following article was adapted from the CrossFit Medical Society Newsletter. Visit them to learn more about the society and become a free member.

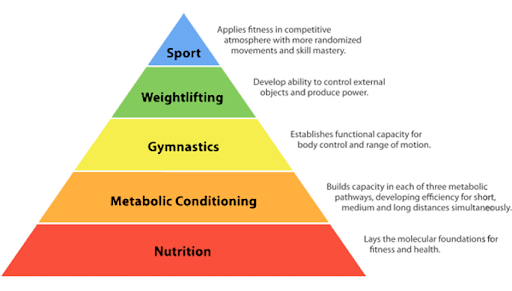

In 2002, CrossFit Founder Greg Glassman wrote the seminal article “What is Fitness?” and outlined the Theoretical Hierarchy of the Development of an Athlete. This ranking, ordered not by CrossFit but by nature, illustrates that each layer is dependent on the supporting layers below. Nutrition — the inputs to the system — is placed squarely at the foundation.

In the same article, “World Class Fitness in 100 Words” begins with the now infamous line: eat meats and vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, no sugar. Consider this for a moment: In the prescription for achieving world-class fitness, the first line has nothing to do with exercise or training at all.

It tells us what to eat.

But before we dive into the details, we need to zoom way out to ponder a big-picture question:

Why do we need to eat? What is food for?

When asked this question, most people will respond with an enthusiastic “Fuel!” or “Energy!” and while these answers are correct, they are incomplete. It’s true that food provides hydrocarbons (fats and carbohydrates) that get turned into ATP (the energy currency of the body). But just as important, if not more so, food also provides building blocks — structural elements that do not get used for energy but instead get turned into our brain, muscles, bones, connective tissue, blood vessels, neurotransmitters, etc. Every bit of you is built out of something you ate. Saving the energy topic for another day, in this article, we are going to explore the under-appreciated but very necessary structural elements of the diet to create the muscles and bones we need for work capacity across broad time and modal domains throughout the years of our life – i.e., health.

In CrossFit’s nutrition recommendation, “eat meats” is offered as a placeholder for animal products in general — meat, eggs, fish, dairy, etc. The primary macronutrient in these foods is protein. When consumed and digested, dietary protein is broken down into amino acids. Think of amino acids like Lego blocks and proteins as the near-infinite number of creations we can construct out of them. There are 20 amino acids used to build proteins in the human body, nine of which are essential (meaning we have to get them from the diet) and another six that can become essential depending on factors such as training volume, illness, injury, etc. From these amino acids, the body produces at least 20,000 proteins that we know of. Some are small, such as the hormone insulin constructed of just 51 amino acids linked together. Other proteins are huge. Titin, found in the sarcomere of muscle, is the largest protein in the body and is composed of approximately 34,350 amino acids!

Muscles

When we work out, we cause damage to muscle tissue as muscle fibers break down under stress. In the days that follow, our body uses the protein from our food to repair the damage, producing tissue that is stronger than before and better prepared to handle that demand again in the future. One amino acid in particular, leucine, triggers this process of muscle protein synthesis more than the others. We find high concentrations of leucine in whole foods like beef, chicken, pork, tuna, salmon, cod, and cheese.

While more thrusters and a bigger clean and jerk are cool, as we progress through the years of life, our muscle mass and muscle function become the single greatest predictor of how well we will age. A “health pension account” of sorts, muscle has been dubbed the organ of longevity. Muscles are the primary organs for glucose disposal, helping us maintain healthy blood sugar levels and avoid Type 2 diabetes. It sends signaling molecules to the brain that keep us sharp and mentally flexible. And, of course, muscle is the most important inoculation against decrepitude, the loss of functional capacity that robs a person of their ability to live independently when they can no longer get up off the toilet, navigate stairs, and carry their own groceries. In fact, low skeletal muscle mass has repeatedly been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of all-cause mortality, which is to say who will die of anything.

In short, more muscle = less dead.

Bones

Bones might seem like solid, unchanging structures, but like our muscles, they are living tissues constantly being broken down and rebuilt.

Calcium often comes to mind when we think of bones, but did you know that approximately 50% of the dry weight of bone is actually protein? In the form of collagen, this protein creates the structural matrix of bones (to which the minerals calcium and phosphorus attach, like spackle). Collagen gives bones both the compressive and tensile strength needed to support the body’s weight and withstand huge forces — an amazing tissue on par with the strength of concrete!

Adequate protein intake is essential for bone formation and remodeling. Collagen requires large amounts of an amino acid called glycine, along with proline, hydroxyproline, and lysine. We find rich sources of these bone-building amino acids in foods cooked on the bone, such as ribs and roast turkey, and with the skin on, such as fish or chicken. Bone broth, a traditional food found in many cultures worldwide, is also a wonderfully nutritious source of collagen-building amino acids and can be made from beef, pork, poultry, or fish.

Diets that lack these foods are associated with lower bone mineral density (BMD) and an increased risk of fracture, while people who get more of their protein from these foods tend to have higher bone density. The source of our dietary protein matters for bone health, as does getting a high total amount of protein, especially for older adults. One analysis found adults aged 70-75 in the highest third of protein intake had higher BMD and lower risk of vertebral fracture when compared to those in the lowest tertile of protein intake. As we age, a major bone break becomes not just an injury but a serious mortality risk. Follow-up on 758 adults over age 60 who fell and broke a hip found that more than 1 in 5 were dead within a year.

In short, stronger bones = less dead

Summary

Highly nutritious whole food sources of protein from meat (as the catchall term for beef, pork, chicken, seafood, dairy, etc.) provide the essential structural elements in the diet to build the strong muscles and dense bones we need to maximize our work capacity across broad time and modal domains. Across the years of our lives, those muscles and bones we built up allow us to not just survive but thrive, tackling any adversity or taking on any adventure that comes our way well into our 80s and 90s.

aBOUT THE AUTHOR

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) has been running a CrossFit affiliate full-time with her husband since 2008, gaining extensive experience in nearly every aspect of affiliate ownership and coaching. She coaches 15-20 hours/week and travels regularly to lecture as part of her role on CrossFit’s Seminar Staff. Jocelyn has a Master of Science in Human Nutrition, and her journey as a coach, student, and athlete is a testament to the principle of following your passion and not fearing change. Her integration of research and teaching is a perfect complement to their affiliate and serves as a model for many who aspire to do the same.

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) has been running a CrossFit affiliate full-time with her husband since 2008, gaining extensive experience in nearly every aspect of affiliate ownership and coaching. She coaches 15-20 hours/week and travels regularly to lecture as part of her role on CrossFit’s Seminar Staff. Jocelyn has a Master of Science in Human Nutrition, and her journey as a coach, student, and athlete is a testament to the principle of following your passion and not fearing change. Her integration of research and teaching is a perfect complement to their affiliate and serves as a model for many who aspire to do the same.

The Primer on Protein for Health Across the Lifespan