As predictions are the ultimate end of scientific models, validation (or the lack thereof) of a model’s prediction(s) is the ultimate end of scientific experiments and will serve as the focus of this final post in our consideration of the seven elements of science.

Recalling previous discussions, we reiterate that scientific models created from real data or by reasoning from real data must admit validation. This validation confirms or verifies the model’s predictions of qualitatively new phenomena or relationships.

Recalling previous discussions, we reiterate that scientific models created from real data or by reasoning from real data must admit validation. This validation confirms or verifies the model’s predictions of qualitatively new phenomena or relationships.

We also recall that prediction is proposed as the ultimate objective for science, which must do better than chance to a prescribed error level.

Validation, then, is the ultimate process of demonstrating the predictions of scientific models. It consists of devising experiments, gathering confirming or denying data, and evaluating the model in question. The predictive value of a model includes a measure of accuracy in the prediction (though not the utility of the prediction).

When the prediction introduces a novel cause-and-effect relationship, a confirming experiment introduces a degree of validation. This is confirmation but of a prediction. The model, while not yet certain and destined never to be certain, is stronger. Facts exist where previously there were none. An instance of validation often becomes part of the domain of the model in a larger context. If the data simply reproduce data already in the domain, they contribute to the accuracy estimate of the supporting data. If the data are unique and still fit the model, the domain of the model increases.

Creativity and Validation

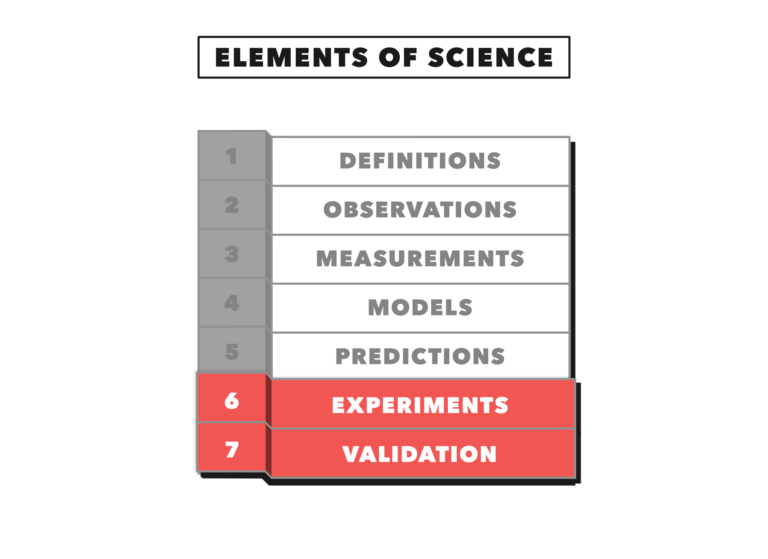

We recall that in our organization of the scientific method, the element of “experiments” was split between the categories of “creativity” and “validation.”

Constructing a validating experiment often requires interpretation, skill, and creativity on the part of the scientist. Science reserves its greatest rewards for the scientist who conceives of an especially clever experiment that either validates a new theory of breadth or disproves a well-established one.

So, does validation begin with the invention of the experiment, or does the experiment belong with the creative process? Even making the prediction or finding it in the model can be a consequence of experimental design. Often the initial formulation of a model does not include what later develops as a major consequence or prediction. Quite often, the predictions of the model are consequences discovered by scientists other than the creator of the model. Placing experimental design under creativity reinforces the objective of emphasizing the creative element of science. The data acquisition phases of experimentation can stay with validation.

Revisiting Model Grading

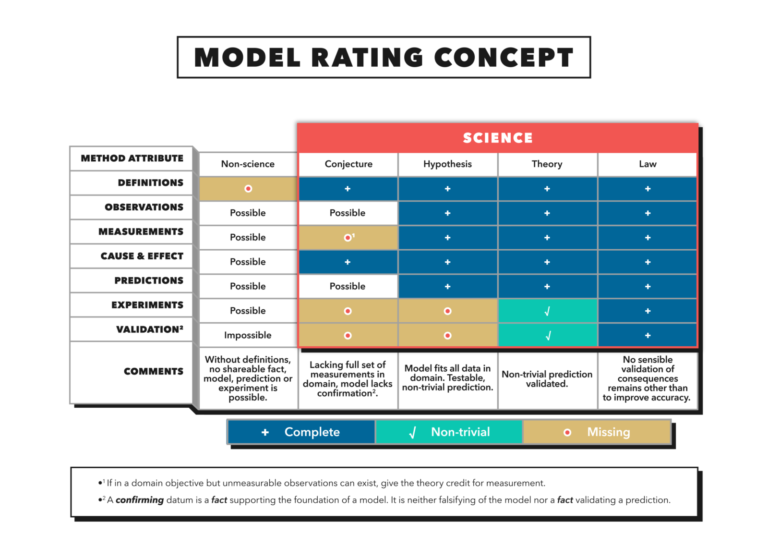

Validation is an essential element of moving a particular scientific model along the progression of conjecture, hypothesis, theory, and law. For example, a theory is a hypothesis that has at least one instance of validation. One fact has met all the premises of the hypothesis and confirms the prediction of the model. Put another way, this instance of validation, discovered via experimentation, has moved the model from hypothesis (a model based on existing data, making a non-trivial prediction that is as yet unvalidated) to theory.

This chart (taken from Jeff Glassman’s 2019 article “Rating Scientific Models”) provides a helpful visual of validation’s role in rating or grading scientific models.

A Note on Validation

It should be noted that often validation is not as straightforward as these discussions might indicate. It is not as simple as measuring the degree of bending of starlight around the sun. As science advances, scientists create models of phenomena more and more deeply embedded in noise. As the easy models become part of the history of science, the new models encompass more uncontrollable phenomena that can mask a direct observation of the prediction. This is particularly true in epidemiological studies. The experimental design problem in assessing these phenomena challenges the creative skill of the scientist more than developing the original model.

Many models never reach fruition as a theory because of the conceptual problems in designing a method for validation. Nonetheless, many marginal models manage to affect public policy and national well-being far beyond their predictive power. The impact these flimsy, conjectural models are having is a measure of the prevailing low level of science literacy in America and the world at large.

Elements of Science: Experiments & Validation